PALESTINIAN WOMEN’S WORK: A HANDMADE STORY

Sometimes you hear the news... and you know that there’s a war going on...

you find the news unbearable... Yet you have to absorb it like a bitter drink...

Sometimes you think about the war and you wonder if humans

deserve to be called the best creation of God on earth...

Sometimes you think of all the olive trees in the Middle East and wonder how many

more you need to plant so that peace could exist... And you make yourself believe

that tomorrow will be better... although you know that this will happen again and again...

Sometimes you wonder why anyone would want to destroy anyone?

Sometimes you look so calm while people in Gaza are butchered...

Sometimes you wait for a reaction... You lose patience and curse... you breathe

with difficulty... and are puzzled: why have you not yet died from rage?

Sometimes you feel guilty while having lunch... and you think of hunger...

Sometimes you have to admit that pain exists... and that you feel worn out...

Sometimes you avoid the news... and you say nothing... and do nothing...

But at other times... you think of the children... of the women... sitting by the light of an oil

lamp... stitching... they let the stitches speak... there’s love for life... and a desire to be alive...

In their patterns you never see death... but you see a flower, a tree... a sun...

a foreign moon... And birds waiting to return... you see belonging... and you let yourself

be embraced by the stitches... hearing their hidden language... and you admire these

women... and you decide to do something... to stitch...

Embroidery can involve a private, quiet time for some women. But for Palestinian women, embroidery connects

them to their history before the diaspora and their complex problems since the diaspora. Each motif has a name

which links it with a particular location prior to the diaspora. In these patterns one can, for example, see an Olive

Branch, the Key of Hebron, the Tiles of Bethlehem, and the Mountains of Jerusalem. Palestinian embroidery is not

only a material practice, but also a way for the women to connect with their history, to keep it alive and to speak of

their geopolitical loss. Through slow stitching which involves a contemplative state, they celebrate and grieve.

In 1967 my friend’s mother Ghazieh was stitching a dress for herself in a village called Aldawaymeh near Hebron.

Then the war happened and they had to evacuate their village and flee to Jordan, and she never had her dress

finished. She only made the front panel which she wanted me to have when I got married and she said I will know

what to do with it. This piece stayed in my closet for four years until my graduation last year when I decided to

bring it back to life..

In her stitching Ghazieh used a few motifs: Eye of the Cow, Cypress Trees, a Saw, and Flower Pots. These are

mainly from the Hebron area. But the shade of the red thread – which is a wine red – was used in the Jaffa area

and not in Hebron.

The Cypress Tree motif is one of the most popular in all the areas of Palestine, and it takes a variety of forms in

different geographical areas. The vast range of possibilities for arranging the stitches in so many different ways is

really what the art of the needle is all about. It has rules of structure; it has stability; it has a system; it creates by using

the elements of a language; it consists of signs and meanings which we can understand if we learn the code.

Inspirations for patterns have come from the most beautiful carpets, from mosaics and tiles, from ceramics, printed

fabrics, and even from architectural motifs. Many of the names of the designs come from peaceful village life,

examples being Bridal Comb, Bottom of the Coffee Cup, Chicken’s Feet, Chick Peas and Raisins, Four Eggs in a Pan,

Soap Slices, and Old Man’s Teeth! Other names are deliberately humorous, with a social commentary embedded

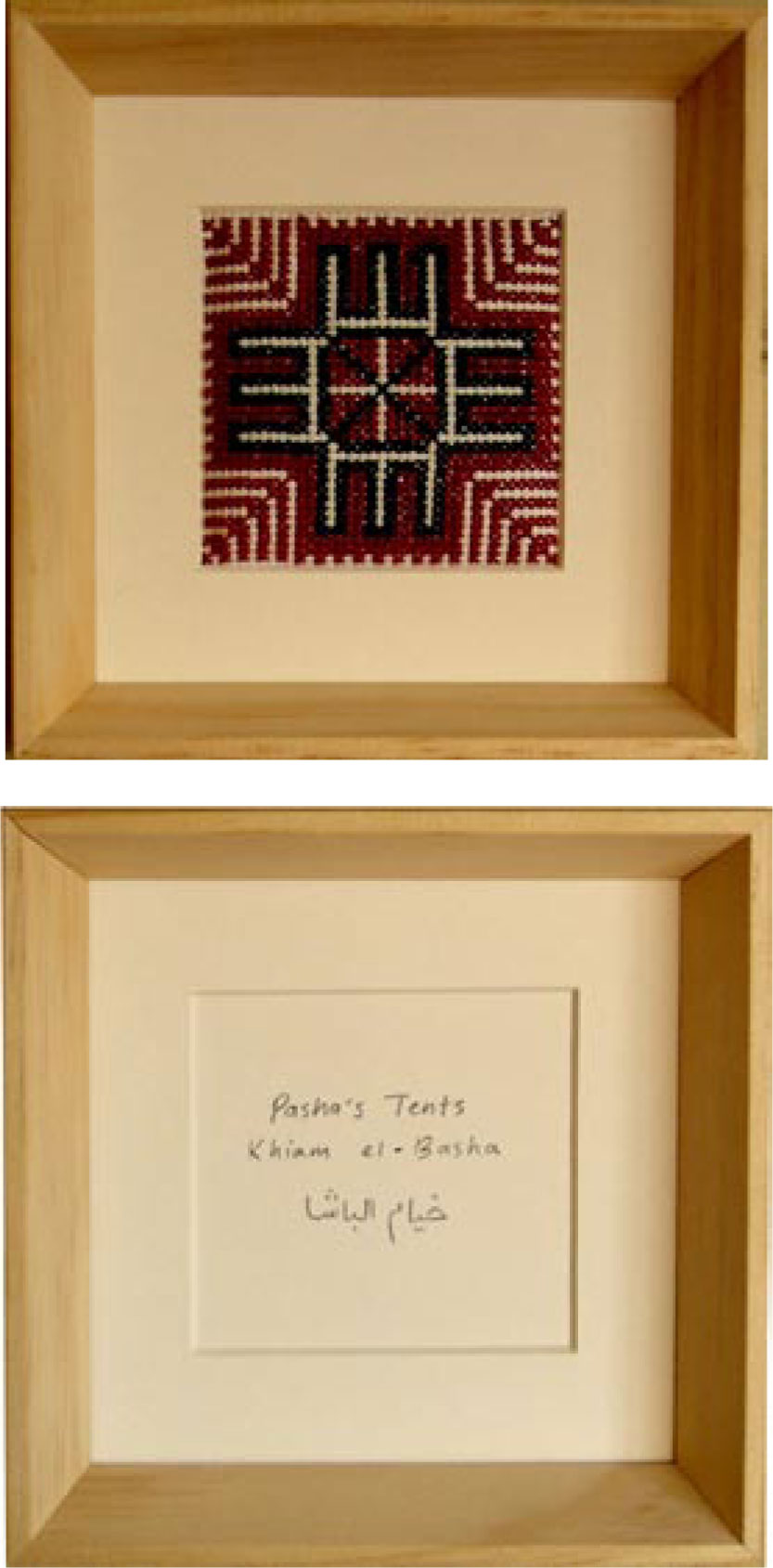

in them. Two birds facing away from each other could be “a young woman and her mother in law”. And yet other

motifs refer to millennia of foreign occupation: “Pasha’s Tent” being a reference to Ottoman times; and “Officer’s

Badge” being a reference to British mandatory military uniforms. Often different generations and different villages

use a different name for the same motif. A daughter, for example, could alter a pattern slightly and rename it for

herself.

I have been stitching continuously. Sometimes I sit for hours and stitch until I become like a dervish – unaware

of what am doing, unaware of time. I stitch till my fingers hurt and then I pause and I think of Palestinian women

stitching… what do they think of? I think these women will be asking themselves while stitching: Who we are?

Where do we come from? And where are we now after the Palestinian diaspora?

Stitching can be a way to heal… a way to mourn…or a way to erase that moment of departure… that moment

when they had to leave. But also, the patterns tell of history and for Palestinian women they are like maps which

pull them together, connecting them. Although something has been lost, the representation of loss can sustain them

to some extent. This representation through embroidery is what they still have. For the older generation it speaks

of a life, of a place, of stability, of geography. Now these things have completely disappeared. But the loss of the

real Palestine has given birth to a Palestine of the imagination, a Palestine that can be materialised through the use

of thread and needle. The women will always long for the real Palestine, but they will never lose the Palestine that

exists in the inner world of their memories…and the importance of embroidery for them lies in how it helps to fill

the gaping holes in their hearts and to clear the blurred images in their minds.

We embroidered the side panels for such a long time! remember Halimeh when we were pals? We embroidered the chest panels for such a long time! remember Halimeh when we were girls? Henna Night Song, Beit DajanPalestinian embroidery is not only unusually beautiful. It also tells stories. It is often assumed that Arab women have no say. But the women who have embroidered these dresses, who have chosen their own designs, have also chosen the statements their works make.

And also, there’s something really positive about these women. These women do not give up, even though most of the world has given up on them. These women are saying something. They may not have the ability to make huge decisions, but they can still decide what colour to use, and which pattern works better with which design. These women are being creative even if this creativity derives from blurred memories of place or from dreaming of a better life. These women make a powerful impression on me…and I think I will be stitching for some time yet.Lamis Mawafi immigrated to New Zealand from Jordan in 2003 and is a Master of Fine Arts graduate from Otago Polytechnic, Dunedin, New Zealand. She works mainly in the textile arts. She is currently involved in an embroidery project which identifies themes of peace and war by engaging with the plight of Palestinian women in the Middle East